This book has been written for all those who love the musicals of Boublil and Schönberg and for those who have a more general interest in the creative process of musical theatre.

Here you will find very brief extracts from each chapter.

Chapter 1

A Question of Identity: A Biographical Portrait

Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schönberg are both intensely private people. Everything that has been written about their personal lives to date would fit on a postcard. Although Alain and Claude-Michel both consider themselves to be technically French and speak French as their first language, they have no real affinity with or allegiance to France, and feel equally at home anywhere in the world. There are many surface differences in their early lives. Alain grew up in Tunisia and Claude-Michel in Brittany; however, there are also many fundamental similarities. They were both born towards the end of the war, their families were Jewish émigrés and both their lives, to some degree, have been shaped by political situations. Alain’s family had emigrated from Egypt to Tunisia and Claude-Michel’s from Hungary to France, so throughout their childhood there was no sense of old family roots or of being strongly connected to any one place, and both men have a deeply felt sense of rootlessness. Both were very ambitious from an early age and soon felt restricted by the limitations and smallness of their hometown environment.

… When Alain moved to Paris, it opened up a whole new world for him. He became a student of the Institute of Higher Commercial Studies and after three years he graduated in Economics. It was, however, a very elitist establishment. AB: It’s the kind of school where people go who are going to run the country. They were mostly the sons of the very wealthy – the people who owned all the factories, the champagne people, even the son of the King of Thailand. We were lost there. We were completely out of their league and they looked on us with contempt. It didn’t really concern me, but I just thought that one day we would top them with something else!

Nevertheless, Alain loved his student years in Paris. He lived in a very cheap, small student house in the fourteenth district and in his first week he walked Paris completely, discovering every district for himself. So what was his first impression? AB: I remember thinking that I had never seen as many beautiful girls at the same time, in the same place, on the same day. It took me years to recover from that! That’s the main thing about Paris when you are a young boy. It certainly wasn’t like that in Tunisia. In Paris we enjoyed the freedom, the café life, the university and all those different things …When I began my studies I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. It was just a way for me to delay the decision … But the pop revolution was a new era and I was part of it. I was even the same age as the Beatles. It was something I could really identify with, something that made me think – “This is what I want to do. I want to work in the music world”. So that’s why, when I finished my studies I didn’t go into a bank or any other serious institute, but to a radio station called Europe Number One, where all this revolution was really happening.

… Claude-Michel’s parents were not very well off financially but they were very rich in a cultural sense. Before they settled in Brittany they had lived in Budapest, one of the main cultural centres of Europe and that was the kind of life Doli and Juci were accustomed to. CMS: We had Madame Butterfly, Carmen, The Tales of Hoffman and we had the Beethoven Symphonies too. But each opera was a suitcase! There were twenty to thirty records for one opera and each side was only three or four minutes long. But I loved playing them all the way through … I can remember one day, when I was quite young, young enough to have to hold my mother’s hand, she took me to a new department store in our town. It had just opened and then it seemed so big, it seemed like paradise. They had loud speakers for music and advertisements. We were going up the stairs and suddenly I heard this music over the noise of the crowd. I stood completely paralysed, listening to this wonderful music, it vibrated through me. I didn’t know that anything so incredibly beautiful could exist. It was years later before I heard it again and learnt that it was the Prelude for Strings in Wagner’s Lowengrin. I can also remember my mother yelling at me for standing there because she was worried I’d be lost in the crowd.

… I remember my brother winning a competition in which the prize was a year’s subscription to Life magazine. It was a complete revelation to me, the kind of life that it showed. It was full of gorgeous people with big houses and big American cars and it showed a high standard of living. It was a dream world. I remember there was an advertisement for cigarettes, which showed the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. It looked so beautiful but I thought I would never be rich enough to go there. Years later, in 1975, when I first went to San Francisco, I hired a car straightaway and drove over the bridge so I could see myself in that picture. In fact I did it three times.

… Claude-Michel took piano lessons for six years, but with some reluctance because he never learnt to read music and he couldn’t see the point of playing other people’s music that had been played millions of times before. He only wanted to play his own music. His music teacher thought she was teaching him to play the piano from printed sheet music. CMS: But I never told her that I wasn’t reading the music. I didn’t make the effort to learn to read music, so each week after the lesson I used to come home and re-do what she had done. I learnt it by heart in an hour and I could reproduce it exactly. So the next Thursday I would go back with my sheet of music and play, and she never knew I wasn’t reading the music. I told her in the end, when I was giving up my lessons, and she was very surprised because each lesson she thought that I had been working hard all week to get the music right.

… Claude-Michel loved the big city life and everything about Paris. “When I arrived in Paris I felt like the King of the world.” It was where he wanted to be and it was the beginning of a career in music. It was an exciting time in the mid-sixties for a young man to be producing records, writing his own pop songs and meeting a lot of interesting new people who were all involved in various ways in the music industry.

When Alain and Claude-Michel met in 1968, it was not, however, through their respective work in the music industry. Their meeting, as much of the story of how their musicals came to be written, was what Claude-Michel describes as: “a matter of chance and will” ……………

Chapter 2

Do You Hear the People Sing?: Writing the Musicals

Alain and Claude-Michel are essentially musical dramatists, that is to say that everything that they write is motivated by the story. When they start working on a project together there is no division initially between lyric writer and composer, for they are both “book” writers. They spend several months telling and re-telling each other the story visually, and not until they are completely satisfied do they write a word of the lyrics or a note of the music. It is through this process that the subject is allowed to grow and develop with a single vision.

CMS: …It’s always difficult for us to choose a subject for a show. I don’t have any particular criteria but I must be moved or have a sparkle and it must be a wonderful story. Of course I have to deal with emotion, passion and real people’s lives, not in an intellectual way but with all the deep fibres of human feeling. I know I will never write a show about a painting, I don’t know what to do with that kind of subject. It’s very important to Alain and me that we do something different each time that is not a straight repetition of what we have been doing before. We’re trying each time to be heading to another territory of music or style, and even if that’s not true of the final result we have to believe that’s what we are doing. You have to be able to surprise and excite yourself with something new every time.

… AB: After several drafts we end up with a script that is somewhere between the book of a musical and a movie script. It tells the story in detail and we describe every scene exactly, working out everything dramatically. We know where the main songs will be and what the emotions are, and even when a song will be reprised. We know where a reprise will be even before the song is written because the situation demands it. So we have a kind of synopsis to start with of how the musical will eventually be. But you can imagine the first version of that is very naked. It’s very different from what it will be at the end. We enrich it and we add to it every day, every week, so every idea finds its way through the script until we have a story in seven or eight pages that we can read and be pleased with.

… CMS: When the first draft of the story is done I can start thinking about the music and the sound of the music. Quite simply what I want to do with the music is story telling. In the choice of the subject and even sometimes in the title you have a sense already of what kind of colour the music will be … I try to start writing the music chronologically from the beginning of the show to the end. Sometimes I have in advance one theme or one melody I have already imagined for the show and I will base a whole sequence on this theme. When I begin I know the story I want to tell and what I want to say but I don’t know how. I know the emotion or the feeling this section must bring to you but I don’t know how it’s going to be, I just know how I want it to be at the end of the sequence. I try to imagine what’s going to happen on stage – the set, the lights, what the characters are singing and I have a vision of the shape of the music.

… I write specifically for the story and I can’t take any song from Les Misérables and put it in Martin Guerre or Miss Saigon. I don’t have any songs I keep in a drawer like some composers. I don’t have that system for working and the songs are more integrated into the score so it’s much more difficult to take one song out to stand alone … I believe some people can have the lyrics and straightaway write the music in three minutes. But I have to think a lot and it takes me a long, long time. I have to be at the piano and think and play and then walk about and come back to it. I have to chew it over; it’s like a process of digestion. You have to work every day to try to get it right and it’s always very difficult for me to give birth to a piece of music. I know a lot of people imagine that you’re at a piano and there’s a moon and you have inspiration. But it’s not like that at all; it’s only work, work, work. I can spend a week on three or four minutes of music and generally I play it thousands and thousands of times until the moment I think it’s good and I can tape it.

… AB: In all our musicals it is the dramatic situation that is the most important thing. The music and the lyrics have to tell the story right the way through. Sometimes you have to compromise because the best words will not always be the best words for a musical … However, I like to start working on new material in French so that I can find all the psychological dimensions of the characters and all the implications of the historical period in which our shows are set. It’s easier for me to do that in French because then I can let my mind wander into that kind of intellectual, studious mode which draws on everything I have been reading over the years which has made my culture, which is basically French. So I don’t have to worry about anything other than what I want to say or the way I want the characters to behave. That has become a very intimate process which I can only go through in French. It’s just more natural for me. I know I could do it in English but I would unconsciously be framed by a kind of different behaviour which comes to you naturally when you think or speak in English and it probably wouldn’t give me all the elements that I want to introduce from the beginning in the characters in the play … Some writers say they have a love/hate relationship with writing but I enjoy it fully. In fact I love it. When our work is brought to life on stage I feel reborn.

Chapter 3

Words on the Page: The Co-Lyricists

Alain Boublil: It is very difficult to find a good lyricist because if he has written his own shows then why would he bother to sit in a room with me and work as my co-lyricist? If his ego is too big then he won’t accept that. I need someone who has respect for the original piece I’ve written in French and at the same time someone who knows that I completely respect what he is bringing to the piece and understands that I’m not trying to make him less than he is.

… Herbert Kretzmer, Co-lyricist on Les Misérables: I began working on Les Misérables on 1 March 1985, with only five months to go before rehearsals started on 1 August, at which time my work was by no means completed. This meant working fast and under pressure, but speed is, of necessity, a journalist’s forte … It was not a question of translation. I don’t like the word translator. I don’t acknowledge the term. I don’t speak French, for a start. Transforming a song or a musical is not like translating a textbook or a novel, where absolute fidelity to the original is required. With a song you are re-inventing an idea, a phantom, a fiction made up of words and images which have a particular resonance within a specific culture, to whose members you are appealing. Every culture has its own tribal assumptions, its own linguistic nuances. Lyric writing is not about stating the obvious. It seeks to set in motion a certain trail of wonder and imagination, to hint at something lurking beneath the surface.

… Richard Maltby, Jr., Co-lyricist on Miss Saigon: Claude-Michel always writes the music first. In this sense he is a true opera composer since the primary dramatisation is his. The music shapes the scenes dramatically. Alain and I would always stick to the written music, because there was always something right in it … “The American Dream” was a fundamental theme of the show right from the start, but it gave us one lyric problem. “Le Rêvé American” was the original French title for the song which became “The Movie In My Mind”. The French title fitted this melody perfectly but “The American Dream” didn’t. I wanted to keep the French title, because after all Gigi, who sings it, is French. But Alain felt strongly that it absolutely had to be in English. The line, “The movie in my mind” was a line in the second half of the song in an early version I wrote to audition for the job. The American Dream is, after all, transmitted around the world by American movies. Cameron said, “That’s the fresh thought”, so we focused the song on that phrase. But now the actual phrase, “The American Dream” didn’t appear anywhere in the script. The production number near the end of the show was originally quite different, it lacked a lyric and a concept, and we wanted to rewrite it – but we couldn’t find a good title! Then one day Alain realised that that melody exactly fitted the words “the American Dream”. It had just been sitting there. We’d missed it, and it’s the perfect setting. We were thrilled, though I will admit that, as an American, I always felt I should have been the one to come up with the idea!

… Stephen Clark, Co-lyricist on Martin Guerre: There aren’t many composers that understand dramatic structure as well as Claude-Michel does. And that is why their musicals are sometimes referred to as musical operas. A lot of musical theatre composers can write terrific tunes but they don’t always fully understand the need of a dramatic impetus or momentum. Claude-Michel is as much a book-writer as a composer, and that’s rare, but it means that the music always has a dramatic reason, rather than just being a great tune. The fact that they are also great tunes is wonderful, but you are getting both, and I think that’s what makes his work so special. Sometimes the mood and the emotions created by the music are stronger than the words and then lyrically you’ve just got to stay out of the way and not spoil it … Another thing which makes Claude-Michel’s work very special is the way he uses reprises both on an overt and a subliminal level. He will set up a melody in a particular moment to have a particular emotional effect so that maybe half an hour later you only need a tiny moment of that melody to trigger the learnt response to the first time that melody was stated. It’s not a short cut but it’s a very direct route into reawakening the emotional state that was, hopefully, awoken in the first place.

Chapter 4

From Page to Stage: The Directors

One of the most important members of the collaborative team is the director, for he has the task of bringing alive the words on the page to a full visual and dramatic staging. Cameron Mackintosh’s experience and skill in producing musicals has always instinctively led him to proposing the most appropriate directors although the final choice is always a joint decision reached after much discussion with and the approval of Alain and Claude-Michel.

… Trevor Nunn, Director of Les Misérables: Political idealism and religious zeal are both very important thematically in Les Misérables but Hugo seems to be saying that it is possible still to believe in God and still to believe in the future through the operation of human love. The last line, before the final chorus, is “To love another person is to see the face of God” and when that line came from Herbie we knew that we’d got absolutely to the center of the work and had said something that Hugo would be moved by and acknowledge the truth of. But the final chorus goes beyond that perception because, as I have always explained to the performing company, all those who have sacrificed, all the dead re-emerging and joining the living are actually asking a direct question of the audience: “Is this not what you want? Don’t you want a better world or a world to be made new?” The chorus line ends with the phrase “Tomorrow comes” and it’s partly a repeat of the larger phrase “When tomorrow comes”. But that very final repeat “Tomorrow comes” is not just a repetition of two words for emphasis it is an affirmation of the question that Hugo asks at the beginning of the book: “We may be tempted to ask: Will the future ever arrive?” The show finally declaring “Tomorrow comes” is the most felicitous bit of writing in summarising Hugo’s theme, both in terms of the lyric vocabulary of the show and its meaning for an audience. And I like to think that an audience stands up at the end of Les Misérables, as they so invariably do, not only in the traditional way of expressing their admiration of the performers but also to bear witness to this message. That may be pure sentiment on my part but I have felt that surge so potently on many occasions to the point where I do believe a yearning and an idealism is aroused which, at least for a while, displaces our pervading cynicism.

… John Caird, Co-director of Les Misérables: Casting is an imperfect science. You’re not going to find the strongest man in Europe to play the strongest man in Europe. Ultimately you cast the man with the best voice in Europe to play the part. And we were lucky enough to have Colm Wilkinson as our first Jean Valjean, and he created that role brilliantly. You make your decision as to who should play a role and from that moment they are that person. They must have the freedom to act like they act and to sing like they sing. To a certain extent you can propose changes to them and you can involve them in artistic choices but their body, their face and their voice is the raw material you are working with … The actors not only have to get inside the skin of their character but they’ve also got to get inside the skin of the music as a musician, not just as a singer. They’ve got to feel the intensity of the music and let that inspire them. They have to let the musical feel, the rhythm and the content of the lyric define the atmosphere. For instance, in “Bring Him Home” Valjean has got to be passionately praying but he’s also got to let that wonderfully elevating melody imbue him spiritually. In “Stars” Javert has this almost mechanical attitude to the world but the song also has a strong “rock anthem”’ element. A good Javert will feel the rhythm of it coming up through his legs into his body. It’s the rhythm of the song that gives it its emotional rigidity and strength. I think that one of Claude-Michel’s greatest gifts as a composer is the rigour of his songs and that comes from their rhythmic structure.

… Nicholas Hytner, Director of Miss Saigon: It’s the director’s job rather than the writer’s job to visualise how a scene will work. Alain and Claude-Michel put in the flashback scene with the evacuation of the Embassy but they didn’t know how it would work on stage. There was a forward moving beat and it was all there musically but, if I remember correctly, they saw the evacuation as a single scene outside the Embassy compound. However, I wanted to experiment with the idea of presenting it cinematically and cutting from inside to outside. It was essentially the cinematic technique of editing together a shot and its reverse – his point of view, her point of view. It was something I just thought would be a good idea and it contributed to the story telling. It’s what a movie director does. An event has to be staged and if there’s an exciting way of staging it and a new way of telling the story then a director can contribute that. Otherwise the director and the producer both act as editors helping the writers find a way to do something better.

… Conall Morrison, Director of Martin Guerre: The setting of religious conflict is, of course, something I know about only too well. I do know what the raw element of prejudice is about because I’ve seen it and lived with it in Northern Ireland. So in terms of that theme I do understand, rather sadly, what it’s like to see a community tear itself apart. However, as a director you are invited imaginatively and professionally to enter into whatever world the script presents and so I should be able to direct a show about Mormons or Eskimos equally well. The most difficult part about staging Martin Guerre was striking that balance between a period feel and a contemporary energy. It was about maintaining the integrity of that world and that period of history and still making it completely accessible and worthy of a modern audience’s attention and engagement. Spanning the centuries in a seamless way was probably the greatest trick to pull off.

Chapter 5

Master of the House: Producer

The most important person in bringing Alain and Claude-Michel’s three shows Les Misérables, Miss Saigon and Martin Guerre to life has been their long time producer Sir Cameron Mackintosh. Ever since a young Hungarian director Peter Farago first played him a recording of the original French version of Les Misérables he has been the most enthusiastic champion of Alain and Claude-Michel and their work.

… Cameron Mackintosh: I’d like to think that after an audience spends two or three hours in the theatre they leave feeling that they’re different from when they came in. Therefore the material that I most enjoy working on has some substance. The music should be able to tell a story as much as the words. The lyrics must emotionally propel the story and characters, without any fat in the writing. You should be unaware that you’re watching scenery and actors and feel that you’ve been totally pulled in to another world. That’s what I aim for in my productions.

… Les Misérables will probably be the show that I’m best remembered for. And it’s partly because Victor Hugo wrote such an extraordinary story. I don’t think any other musical is likely to be blessed with such a strong foundation. Hugo’s genius was that he wrote a story which touches people in every generation and in every country. The characters that he created back in the nineteenth century have the same power to affect an audience around the world today thanks to Alain and Claude-Michel’s masterly musicalisation. It’s very rare in popular entertainment to have something that is both entertaining, thrilling and moving … The inspiration of the writers is the source of it all. I’m obviously very proud that it has now taken over from Cats as the longest running musical in the world.

Chapter 6

New Horizons: The Pirate Queen and Beyond

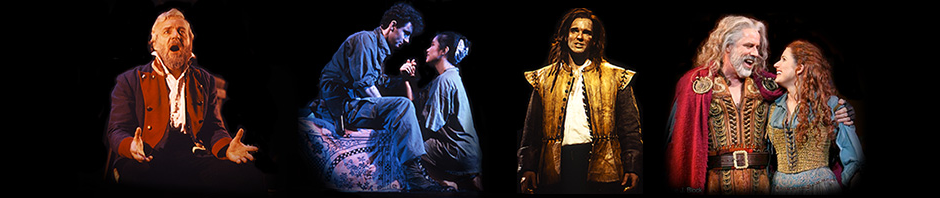

The Pirate Queen is the exciting new Boublil and Schönberg musical, produced by Moya Doherty and John McColgan, who produced the worldwide phenomenon, Riverdance. The musical is based on the real life story of the legendary Irish pirate chieftain, Grace O’Malley.

… Alain Boublil: Claude-Michel and I always spend a very long time choosing a subject for a musical. It’s something we always do on our own, but in the case of The Pirate Queen, for the very first time, it was a project that was brought to us. It was Moya Doherty and John McColgan, the producers of Riverdance, who brought the story of Grace O’Malley to us and initially, we were quite sure we didn’t want to work on someone else’s story. And then we started to think about it and realised that although we hate biographies in musicals we would have liked to write Evita if we’d had the idea first. We could see that this story was just as exciting as the story of Eva Peron and, in a way, more interesting to us, because it’s in period costume and yet it is still more modern than the history of any modern woman today … Claude-Michel was very uncertain but I could see that here was another chance to mix sounds, in the same way that in Miss Saigon we mixed Asian sounds with Claude-Michel’s theatrical, operatic music. Here, we could take those incredible Irish sounds, which are similar to the Brittany sounds that Claude-Michel is so good at, and mix them with the operatic flow of the story, which is such an epic journey. However, Claude-Michel still said: “No, no, I don’t think we should do it” – and the very next day he had composed the overture! When I heard it I said: “Look, we both know we are going to do it.”

… Claude-Michel Schönberg: I didn’t work in the usual way with this show in as much as I would normally give the score to an orchestrator only three months before we started the show. But for The Pirate Queen I started working with the musicians in May 2005, eighteen months before the show opened. And we worked together on a regular basis. Julian Kelly wrote out the music and he has been leading the musicians. I wanted to give them a lot of freedom to interpret the music in their own way. They are working a little bit like a rock and roll band. It’s something I enjoy enormously. It’s a very exciting way to work and it’s an entirely different process to anything I’ve ever done before.

… John Dempsey, Co-lyricist: It has been a wonderful collaboration working with Alain on The Pirate Queen. It was a case of two very different minds trying to come to the same end. Alain and I come from two very different backgrounds, cultures, generations and lifestyles so this was a real challenge and a real joy … Elizabeth is one if my favourite characters and she’s very much in line with my sensibility. She has a very dry sense of humour, a wicked sense of her place in history and a surprisingly sad inner life. I’ve really enjoyed writing for this Elizabeth, who varies greatly from all the other fictional treatments we’ve seen … In some ways she’s the perceived villain yet in the very end she turns out to be a very smart woman, which obviously the real Elizabeth was, and she’s allowed this beautiful moment of grace.

… Frank Galati, Director: I generally prefer not to work out how I’m going to do a scene beforehand but with a show as complex as this the job is bigger than the staging of individual scenes. Many things had to be taken into account beforehand, especially these huge shifts and transitions but also things like lighting cues and even to figure out exactly who’s in what scene, how many are Irish, how many are English, how many women do I have, how many men, and how many women do I disguise as men because I have to have more men on stage in some scenes. Then maybe I have to have all the people who are English in one scene to be Irish in the next scene and I have no time between scenes for them to change. But when I’m working on individual scenes I prefer not to have it worked out. I like to do it with the actors and let the choices that the characters make grow from the actors’ impulses. I try to be their mirror to respond back to them and tell them what I’ve gotten and so on. You can do improvisations and make it up as you go to some extent but of course in a musical you can’t improvise their lines because they’re within a musical structure. But I think that sense of spontaneity and of the unexpected is crucial in the theatre so you are always trying to achieve that.

… Mark Dendy, Choreographer: Dance is very significant in The Pirate Queen but it is always there as a way of forwarding the story. It features in a natural way as part of the life of the people in sixteenth century Ireland because dance was not a performance entertainment but a ritual with roots in its pagan ancestry. The people danced for the harvest, for good weather, to imbue strength into a newborn baby, to celebrate weddings and births and to mourn and ward off the evil spirits of death. I always approach dance from story and place of ritual. The fact that these dances are “real” dances with dramatic purpose and an integral part of our story has been my source of inspiration for creating the choreography in the celebrations for a wedding or a christening and there is a particular kind of stylised choreography employed in the battle scenes.

… Carol Leavy Joyce, Irish Dance Choreographer: For the show we had eight Irish dancers, who had been part of the Riverdance Company for many years, ten modern dancers, a whole ensemble of vocal performers, whose strengths might be singing rather more than dancing, and, of course, all the principals, but what we wanted to see was a rugged, sixteenth century, west coast of Ireland community dancing together. The primary objective was that you wouldn’t see any separation between the groups or different dance styles. We had to find a common vocabulary for the movements so that the different styles would fuse seamlessly to create a complete community dancing together. We investigated many different ways and approaches to each number during rehearsals but we always kept our main objective as the focus, which was to see a community dancing – celebrating and mourning together. We wanted dance to tell the story in the same way that the music and lyrics tell the story. At the same time we did not want to disappoint the huge Riverdance audience who would expect to see wonderful virtuosic Irish dancing.

… Moya Doherty and John McColgan, Producers.

MD: After our success with Riverdance John and I wanted to do another production. We had opened up a gateway to the world, to producing something out of Ireland on a global basis and we felt that the whole profile for organic Irish entertainment was right for following it with something else. But we didn’t want to do another Irish dance show we wanted to do a drama musical. We considered a number of mythological and historical stories but the one we kept coming back to was the Grace O’Malley story. It had a contemporary resonance and a strong female character, who lived during a very interesting period in history and had an intriguing relationship with Queen Elizabeth. The story had an epic nature and it would also allow us to embrace some of the Riverdance elements both musically and with dance.

…

JMcC

: Then we started thinking about who we would like to work with more than anybody in the world. We’re both enormous fans of Alain and Claude-Michel and have seen their shows many times … But it’s my opinion that they’re the best musical theatre writers in the world. They’re the best storytellers and the most eloquent musical writers. They have the most wonderful ability to write and compress a complex historical story and present it with elegance, integrity and intelligence, to write terrific characters and wonderful melodies and to make it into an accessible evening of musical theatre. So we thought: “nothing ventured, nothing gained,” and we approached them with our project.

Chapter 7

Showcase: A fact File on the Productions

The amazing global success of Boublil and Schönberg’s musicals has led to the accumulation of a mass of interesting facts and figures as well as some intriguing trivia.

…Les Misérables is the world’s longest running international musical, which has been seen by more than 54 million people all over the world. It has been translated into 21 different languages and played in 38 countries and 249 cities. 64 professional companies have opened Les Misérables and the production has played over 42,000 professional performances worldwide in places as disparate as Sheffield to Shanghai, Boston to Berlin and Helsinki to Honolulu. The Schools Edition of Les Misérables has played over 1300 school productions in the UK and US. Les Misérables has won over 50 major theatre awards including 8 Tony Awards, 1 Olivier Award, 2 Grammies, as well as the BBC Radio 2 Award for The Nation’s Most Popular Musical and there have been 33 cast recordings.

… Miss Saigon has been seen by over 32 million people worldwide. It has been translated into 11 different languages and played in 23 counties and 240 cities. 26 companies have opened Miss Saigon and the production has played some 20,000 performances all over the world from Memphis to Melbourne, from Philadelphia to the Philippines and from Wales to Warsaw. Miss Saigon has won 30 major theatre awards including 3 Tony Awards, and 2 Olivier Awards and there have been 11 cast recordings.

… Martin Guerre, both the original and the revised version, played in London for 675 performances before the completely new second production opened at the West Yorkshire Playhouse and went on a very successful tour first in the UK and then in the United States. The revised first version won Best Musical and Best Choreography at the 1997 Laurence Olivier Awards.

… The reviews form an extremely interesting part of the production history of the musicals. The excerpts included show briefly the general mood of the reviews and there are a few longer excerpts where critics have given particularly perceptive and valuable insights.

… In this chapter you will find all the details of everything you might want to know about the productions in London, on Broadway and worldwide, with details of the creative teams, casts, musical numbers, reviews, cities played, awards, a discography and some fascinating facts and trivia. In addition to Les Misérables, Miss Saigon and Martin Guerre there are also details of their very first musical La Révolution Française, the original French production of Les Misérables, Claude-Michel’s ballet, Wuthering Heights, their concert One Day More and their new musical The Pirate Queen.

Copyright © 2006, Margaret Vermette except for Chapter 5, which is © 2006 Cameron Mackintosh, Ltd.